The course materials this week on information processing and memory got me to thinking about the strategies musicians use to commit music to memory. I wonder: does honing one’s memory skills as a musician lead to improved overall ability to store and retrieve memories? Do musicians have an edge in the memory olympics?

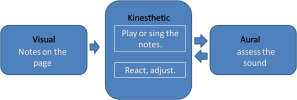

In her paper on Correlating Musical Memorization styles and Perceptual Learning Modalities, Dr. Jennifer Mishra explores the possible correlation between musicians’ preferred learning styles and their preferred memorization strategies. An interesting finding in her research was that few of the musicians questioned in her study reported having a uniquely Aural memorization style. The majority reported having a combination of Visual and Kinesthetic memorization preferences, with no Aural component. Many reported a uniquely kinesthetic approach to memorization. I have tried to illustrate my own personal approach to memorizing in the graphic below.

I have to do something with what I see in order to produce a sound. I then react to the sound by adjusting what I do (practice, practice!). It seems to me that the bulk of the process is Kinesthetic, but I don’t quite understand how people manage the process without the Visual and Aural components.

I know a very gifted young pianist who is able to accomplish quite a bit in terms of memorization without the Aural or Kinesthetic components. I once watched Jack study a piano score for half an hour or so. Hours later, when he finally had access to a piano, he was able to retrieve what he had committed to memory, and could play the passage flawlessly.

Of course, one could argue that the Aural component was indeed present in Jack’s approach, though it was not apparent to the observer. This skill of inner hearing is called audiation. Jack has very strong inner hearing ability, but most of us can do it to some extent. Try this little experiment to test your own audiation abilities: Imagine that you hear the song “Row, Row, Row Your Boat”, being played on a Tuba. Now, play it again, but this time hear it on a violin. Can you hear the difference in Timbre (Tone Color) in your inner ear? Try again, but this time without the musical element. Hear the sound of your mother telling you that dinner is ready. Now, hear this again, but this time hear it in your best friend’s voice. Can you inwardly hear the difference? This is an example of audiation. It is a skill that musicians often use in an attempt to “pre-hear” a desireable tone quality.

I found an interesting article about musicians and memory on a site called SingingWood. A post on the singingwood site addresses strategies for practicing with the goal of improved memorization. One suggestion from the author is that memorization, and, by extension, musical improvements, will be enhanced by frequent short practice sessions. I have found this to be true in my own practice, and I encourage my students to practice this way as well. I would rather see my beginners practice seven days a week for five or ten minutes, than to have them practice once for an extended session. My experience is that the more “visits” to a particular passage, the more likely I am to commit it to long-term memory. Isolated longer practice sessions don’t seem as effective. This may be because of the crowding of too much information into working memory. We tend only to retain the few things that we did at the end of the session. The author also recommends a technique called “Divide and Accomplish”. The idea here is that the chunking of a piece into smaller, manageable sections allows for easier memorization and retrieval. As the small segments are mastered, they become committed to memory and are easily retrieved when the time comes to link the segments together. This concept (chunking of material, in order to avoid cognitive overload) is easily transferred to non-musical attempts at memorization. From an instructional design standpoint, it would indicate that a limited amount of new material is preferable.

I found an editorial from a newsletter entitled “Medical Problems of Performing Artists”. In her essay, , Dr. Alice G. Brandfonbrener questions the tradition of performing music by memory. She points out, quite rightfully, that the added burden of committing music to memory can cause extreme, sometimes incapacitating, performance anxiety. Dr. Brandfonbrener suggests that memorization is irrelevant to musical performance, and recommends taking performers off the hook in the name of a more satisfying musical experience for performer and audience alike. In terms of public performances, I would tend to agree. Still, I can’t overstate the importance of memorization in the initial learning of a piece of music. I believe a musician’s ability to commit passages to muscle memory frees the conscious brain to make choices regarding interpretation and musicianship.

Memorization may, in fact, be an “extra-musical” skill, but it is a very powerful tool in the musician’s arsenal.